China’s Social Credit System (SoCS) is still not a unified standard system used all over China as expected in 2020. What has been established is a policy framework that encompasses a large number of initiatives, both private and public and often different from city to city. A report describes the state of the system, which is measuring and either punishing or rewarding the behaviour of not only companies in China but also individuals.

The Social Credit System of China, which is aimed at mainly companies but also at public sector entitites and individuals to make them behave, is only slowly gaining traction in China. It is voluntary for individuals to sign up, and the vast majority has not signed up to it, and thus it is far from widespread, according to a report from March 2021 from Merics – an Institute for Chinese studies.

“A tiny percentage of people have taken part over the three years of development, according to the report. “In Xiamen, only 210,059 users activated their account (or roughly 5 per cent); Wuhu has 60,000 (1.5 per cent), and Hangzhou 1,872,316 (15 per cent) – and even fewer regularly use them.”

In another pilot city, Suzhou, 1.63 million out of 13 million inhabitants have signed up according to a Dutch journalist in China, Eefje Rammeloo. She reports that in Suzhou, citizens can get between 100 and 200 points. The more points, the more trustworthy you are. You can increase your points by donating blood (5 points) and 21 other factors such as if you paid you taxes and other data from public authorities. You lose points, for example, if you drive too fast (1 point) – even though you also pay a ticket for that. You shouldn’t cross a red light, if you want to avoid the risk of losing points, yet it is not clear how many authoritites are using facial recogition to punish those crossing red lights. At least, according to Rammeloo, Suzhou’s authorities have decided never to let the computers make decisions on their own but requires human interference.

According to the Merics report, some cities are trying to get more people to sign up with fringe benefits; 20% discount on a bus ticket, free book lending in libaries or cheap rides on bike sharing, for example.

Are you on the Red or Black List?

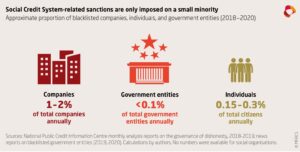

Those who do participate are part of a system, where the data dictatorship defines what is good and bad behaviour. Courts and governments agencies have created a plethora of topical blacklists of serious offenders. Publication of these lists fulfils both a “naming and shaming” and a deterrence function. Logged minor offences can accumulate and be upgraded to a major offence. And SoCS has also established red lists to reward compliant behaviour.

But according to the report, government organs can abuse the system to punish individuals for unrelated behaviour. In Inner Mongolia, parents withdrawing their children from schools with mandatory Mandarin education curriculum were threatened with blacklistings, for example. Government organs or public institutions can also be overeager to use the official “credit” assessment beyond its defined purposes, such as when some public schools decided to exclude students from placement whose parents were on the debt-defaulter list.

Some of the 28 model cities operate well over 20 different blacklists and red lists. The blacklists associated with key areas designated by the central government are relatively well implemented and standardised. For instance, between 70 and 90 per cent of the blacklisted, are people who refuse to repay loans or court-ordered fines while having the capacity to pay.

China Not as Hi Fi as Believed

SoCS implementation – or lack thereoff – in the 28 model cities has highlighted, how many of the fundamentals needed for a genuinely high-tech system, e.g., a shared information system, consistent data formatting – are incomplete. Instead, the SoCS relies heavily on human information collection and low-level digitisation – often little more than the use of Excel worksheets or the WeChat app, says the report.

Little behavioural data is involved, as scoring relies mainly on digitised administrative documents. While early pilots sought to integrate various sources of behavioural and third-party data, this was later discarded.

“Weihai city officials, for instance, decided to exclude data on jaywalking, running red lights, and parking fees from their scoring system. Similarly, Suzhou’s plan to cooperate with gaming platforms to penalise video gamers through the city’s “Osmanthus” scoring system failed to materialise.”

Alibaba’s Work Better

The private tech giant Alibaba has its own credit scoring system, Sesame Credit, based on your shopping behaviour. It has become so ubiquitous that is often conflated with the official Social Credit System, says the report, who underlines that SoCS is actually very transparent as opposed to more covertly related projects such as Golden Shield, or Skynet.

The Chinese government is still working to implement SoCS much better, and the Covid-19 pandemic has shown its flexibility, as it was rapidly deployed in new fields. Model pilot city Zhengzhou for example red-listed all hospitals assigned to handle Covid-19 patients, i.e., basing special trustworthiness on doing what is required. Other cities blacklisted citizens for as little as not wearing a mask.

Given this record, we should expect the system to continue to be rapidly redeployed as new socio-economic policy priorities come up, concludes the report from Merics.