Research: Data collection and analytics have pervaded nearly every sphere of daily life, from commerce to health, from transport to education, to employment. But there is also a rise in intimate surveillance relating to love, romance, and sexual activity. There are sexual quantified self app measuring every moan and thrust. This challenges the very fundamental right to privacy of our intimate lives.

Data-gathering about intimate behavior was, not long ago, more commonly the purview of state public health authorities, which have routinely gathered personally identifiable information to for example fight infectious disease. But new technical capabilities, social norms, and cultural frameworks are beginning to change the nature of intimate monitoring practices. The goal is not top-down management of populations, but establishing k nowledge about (and, ostensibly, concomitant control over) one’s own intimate relations and activities.

nowledge about (and, ostensibly, concomitant control over) one’s own intimate relations and activities.

Here are some examples in the article from Karen Levy in Idaho Law Review:

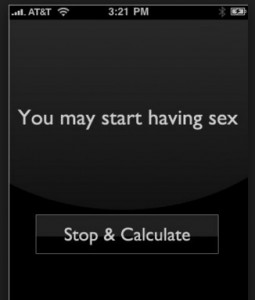

- Spreadsheets captures audio and motion data using the iPhone’s microphone and accelerometer functionalities in order to track sexual performance. Spreadsheets graphs duration, number of thrusts, and audio volume, and allows users to set personal goals and “unlock” achievements.

- The SexFit is a Wifi-enabled ring that sits at the base of the penis (currently in prototype stage) that tracks thrusting rhythm, speed, and calorie burn; the associated iPhone app “tells you whether to slow down or speed up your thrusting.”

- Many sex apps aim to gamify intimate relationships by incentivizing romantic behaviors through points, badges, levels like Foursquare.

- Fertility apps that help women monitor their facility – some of them has now a sexual add-on like the app Glow, which make intimate data collection a family affair. Glow encourages you to sign up your partner to download a “mirror” app; the partner is prompted to provide additional data. Glow gathers such fine-grained and sensitive data as emotional mood, a woman’s position when her partner ejaculates, the firmness of her cervix, and quite a bit more.

- There are period trackers of women intended to be used by men.

- And a huge number of partner “spy” apps like Flexispy, Wife Spy, Girlfriend Spy, Spyera, and ePhoneTracker. The apps are intended to be in-stalled surreptitiously on a partner’s mobile phone, where they run undetected in “stealth mode”; they typically capture a wide range of information, generally including web browsing, phone call and messaging history (sometimes including audio recording), as well as real-time locational data.

- Some of partner-spy-apps are worse than others like the now-defunct Loverspy which was delivered through an electronic greeting card, which (after it was unwittingly opened by a victim) installed malware that was used to capture the content of messages, passwords, and web history; the FBI has since indicted Loverspy’s creators

- Many of these apps are used for domestic violence, revenge porn and other abuse against women.

It’s entirely understandable that there’s a market for intimate surveillance and quantification, writes Karen Levy. But she also states that the intimate areas is uniquely vulnerable, both emotionally and physically. And that:

- But the act of measurement is not neutral. For instance, for sex tracker apps, most smartphones are capable of tracking audio and accelerometer data, so these types of data are what get counted (and constructed as “good” sexual behaviors): “sex is judged by thrusting, success is judged by endurance, and pleasure is measured in moans.”

- The ways we regulate and police intimate technologies are also not neutral, but governed by the socio-cultural realities in which we live.

- Apps that facilitate digital stalking are, essentially by definition,non-consensual and thus a huge privacy risk.

- Data that appear to be shared only within an intimate partnership may also be shared with (or sold to) other parties—including app developers, internet service providers, advertisers, or data brokers and aggregators.

Levy is pointing to that fact that this intimate surveillance can easily become normal. “Consider how normal (and normative) the “Facebook stalk” and other means of gathering predating intelligence have already become; at minimum, Googling a potential partner before dating him or her is essentially social due diligence. We might expect to see other areas of intimate life become increasingly governed by such a surveillant paradigm.”